You may, or probably may not, know that most semi-professional (or, if you're HMRC, hobby) writers, like me, have other lives and proper jobs. For my part, I work as a human resources consultant, words I type with, metaphorically, my hand in the air and eyes to the floor; hearing, but not quite believing, that it's okay, I'm amongst friends.

I actually like the fact that I have a second life; otherwise I fear ending up like the comic shop guy in the Simpsons, self-obsessed, overweight and balding... oh, hold on.

No, seriously, I've seen people like that: there are things about you that you wish could remain forever sixteen years old, but your sense of humour isn't one of them. An external perspective gives you material that isn't in any way related to science fiction to inspire you. You never know where this stuff will take you. Sci-if is a broad church, just as your sources should be.

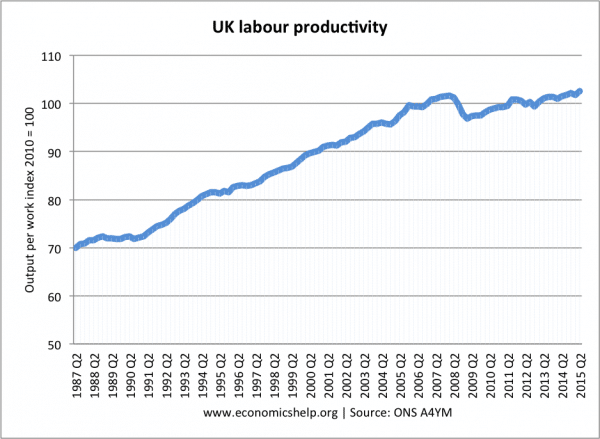

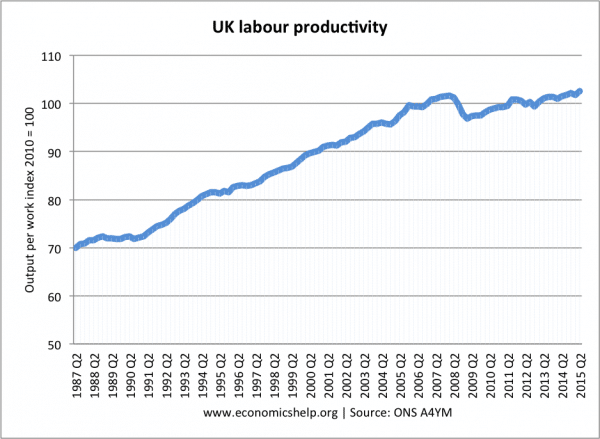

For example, take the productivity conundrum. I could describe it, but a picture says a thousand words (except when you hand in an envelope of seaside postcards instead of a PhD thesis - bastards); just take it as read that what holds true for Blighty applies far wider:

Basically, productivity, our ability to add value in our daily working lives, which took off around the time I entered the labour market and steadily rose for a decade and a half, went into reverse about ten years ago. A lot has been written about what's stopped that steady upward curve. Which isn't going to stop me throwing in my penny's worth.

You see, to me, the answer is obvious. Every generation gets to see a transition; my grandfather's was from horse to car, my father's was consumerism. My privilege was to enter the world of work in an office with only primitive PCs that weren't joined to anything more significant than the mains.

And, boy, that probably explains the initial sky-rocketing of the thick blue line, although I like to think I helped. Being in a paper-centric, desk-bound civil service job, I'm sure the ability to throw away the Dictaphone (old joke: ever used a Dictaphone? a finger's easier) and type the document out yourself impacted on us more than most, although there was a thick strata of dinosaurs who resisted for as long as possible. Primitive e-commerce soon followed for proper organisations that actually contributed to GDP.

I worked through that period of arrow-straight growth when the internet took off and employers, on the one hand, heard the words about how connectivity could transform business and, on the other, busied themselves writing digital usage policies that denied their workers access, although they were holding back the tide.

What was their fear? Distraction. And it came with a vengeance in the form of social media.

Facebook was founded in early 2004, but didn't break out of universities until late 2006. Less than a year later it had 100 million users, which doubled in eight months, and doubled again in another ten.

And, oh look, where does productivity hit the buffers? Exactly in line with the Facebook explosion. Case solved. Facebook destroyed the world's productivity. Or, rather, our primitive desire to share and like pictures of our lunch did.

But don't think this blog is about blaming Zuckerberg - I don't have the budget for lawyers. He was just the biggest surfer with the loudest shorts riding the wave of technology. The

first YouTube video was posted in 2005, and its

history mirrors Facebook, going from a niche for funny cat videos to uber-broadcaster of funny cat videos. And then there's

Google. I could go on and on, but I think the point is pretty obvious.

But not to the commentators.

You see, the error is that people who write books on economic history have a surfeit of intrinsic motivation. They like their jobs. They'd want to write the books even if nobody was paying them. They continue their college lecture to a different audience over merlot and turbot in the evening (see what I did there?). They're not bored at work.

Two things happened. Our employers gave us internet access in the belief that joined-up businesses made for bigger profits. And we all signed up to Facebook so that we could continue pub conversations and YouTube so we could watch cats fall off worktops, or whatever they do. And, yes, we could go hunting for new business leads, but, hey not until we've watched... hey, come here and see what this cat does...

I mean, what an I doing here? I'm meant to be writing another chapter of a science-fiction thriller novel, but instead I'm researching this blog posting? I'm my own employer and even I'm skiving...